Open a business newspaper or webpage of your choice and you will find ample reflections on what the new normal after COVID-19 will look like. And it is undeniably true: The novel coronavirus will have lasting effects on societies and businesses — much like 9/11 brought us new and enduring levels of airport security and the financial crisis of 2008 led to new and continuing financial regulation. But an excessive focus on COVID-19 when contemplating what the future may bring, in our view, is shortsighted. In fact, other trends may have a more fundamental impact. During our “Manufacturing Industries 2030“ initiative that we conducted throughout 2020, we interviewed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of leading manufacturing firms. Emphasizing the need for a broader view, one CEO said: “COVID-19 is not the world — it is the lens through which we currently look at the world.“ And another one put it this way: “COVID-19 itself is not the change, but it is the catalyst for other changes that had already been ongoing.“

Do not look back in anger

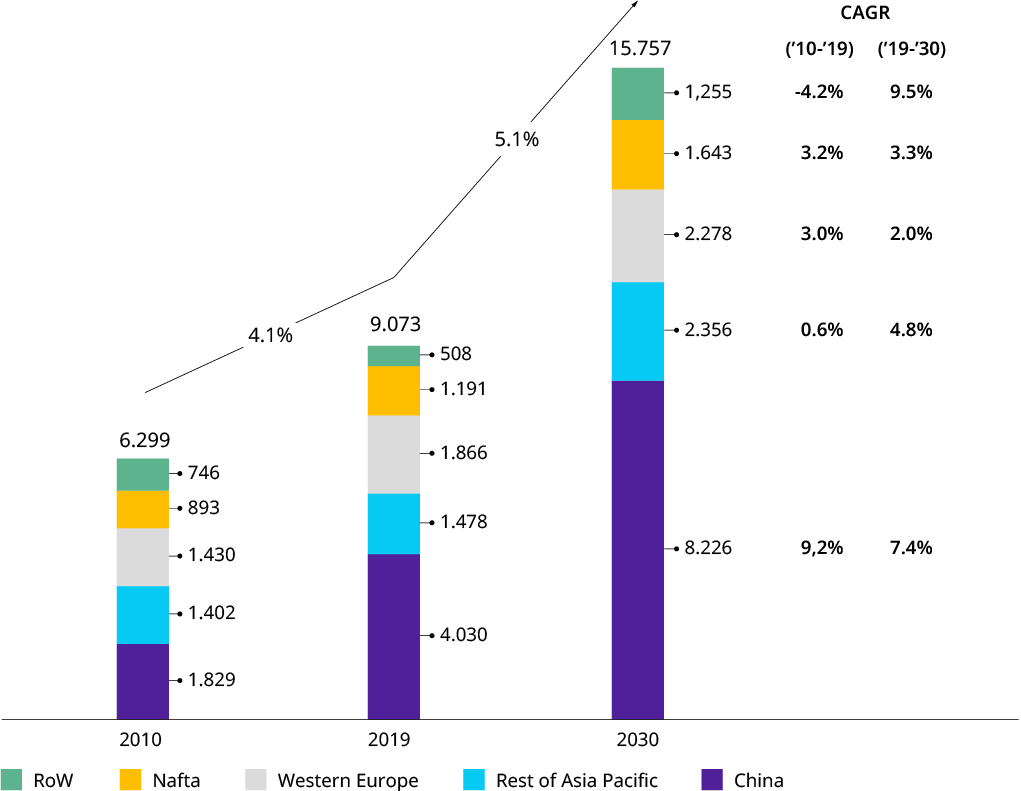

The past decade turned out to be a good one for the manufacturing industry with annual global growth of more than four percent, beating GDP by one percent. (See Exhibit 1.) But it did not start out that way at first. The shock from the 2008/2009 financial crisis led to an overall cautious approach to business in the first half of the decade, and ensuring resilience and flexibility was top of mind for company leaders — an experience and mindset that has benefitted the industry as we entered the COVID-19 crisis. “Digital” and the “rise of Chinese players” were the most prominent trends of strategic relevance. Otherwise, many companies focused more on optimization and operational excellence as well as incremental expansion of their portfolios. While some sectors, such as wind turbine manufacturing or material handling equipment, underwent industry consolidation, it was not a period of industry-shaping mergers and acquisitions (M&A), although the unbundling of several industrial conglomerates toward the end of the decade could be seen as an exception or as the start of a new cycle of M&A activity (also see our hypothesis 8).

Exhibit 1: Past and future growth of industrial goods sector

Global Industrial Goods Output (Sales)1 in $US BN

Engineering & Metal Goods (NACE: 25, 27, 28): Fabricated metal products, electrical equipment, machinery and equipment n.e.c.

Source: Oxford Economics

We asked ourselves, what will the manufacturing industry look like in 2030 — not simply in terms of volume forecasts (as shown in Exhibit 1), but in terms of key structural trends manufacturing firms need to look at. We started the same-named initiative where we established 12 hypotheses on developments that we think have the potential to significantly impact the sector in the next decade. These hypotheses were subsequently tested through a broad survey among executives and discussed in depth with more than 20 CEOs and other management board members of manufacturing companies during the summer of 2020.

The greening of industry

Achieving carbon-neutrality will be necessary yet little differentiating for manufacturers of industrial products — but helping others becoming carbon neutral presents a trillion dollar opportunity

The world is watching

Social media pressure and public opinion hits industrial firms. A rising number of CEOs will find themselves named and shamed for poor corporate environmental and social behavior

The global supply chain dilemma

An ever-increasing array of contradictory and namic parameters (such as trade barriers, political instability, epidemics, and natural disasters) will force companies to square the circle, to actively manage the risks — and to stay flexibleView all 12 hypotheses

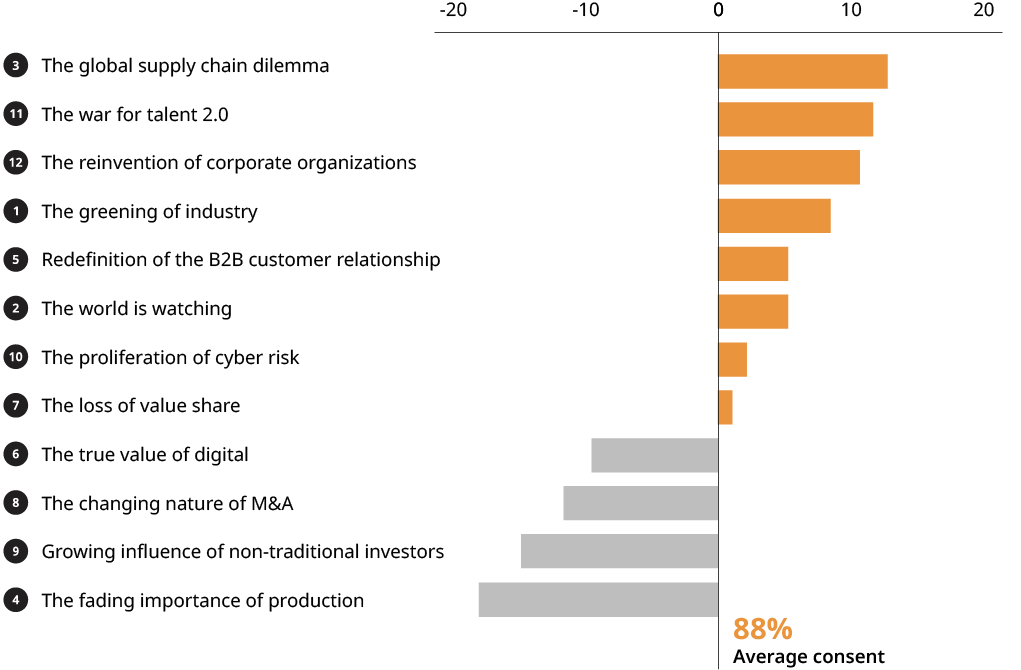

While our approach was global in nature, it has to be noted that the responses were heavily skewed towards Western Europe. Three results are noteworthy: First, on average, 88 percent of survey respondents agreed or partly agreed with our hypotheses. The admittedly provocative hypothesis “The Fading Importance of Production” related to competitive differentiation and future distribution of capital expenditures fell off a bit. Second, many top themes are “known quantities” but have taken on new qualities, either as a result of COVID-19 or through the experience over the past years. And, third, “The Greening of Industry” is the “new kid on the block,” with high relevance and representing a substantial opportunity for the sector.

Exhibit 2: Hypotheses 2030 by relative consent

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

On the last point, as our separate article (“Ride the Green Wave”) points out, this is not about do-goodership or compliance. According to our estimates, it is a trillion-dollar business opportunity for providers of industrial equipment. Depending on how carbon pricing regulation plays out it can be a massive value pool for equipment suppliers who can provide equipment or upgrades to current equipment, which reduces the carbon footprint of equipment operators (for example power generation, steel, cement, and chemicals).

New breakthrough technologies (for instance around hydrogen solutions) and hence new types of industrial equipment that will need to be brought to industrial scale offer the opportunity for manufacturing firms to diversify and get a share of the pie. The fact that richer countries, especially in Europe, will likely drive the climate agenda earlier and harder, gives Western manufacturers the opportunity to be first movers, positioning themselves early for subsequent global rollouts.

Views from the top

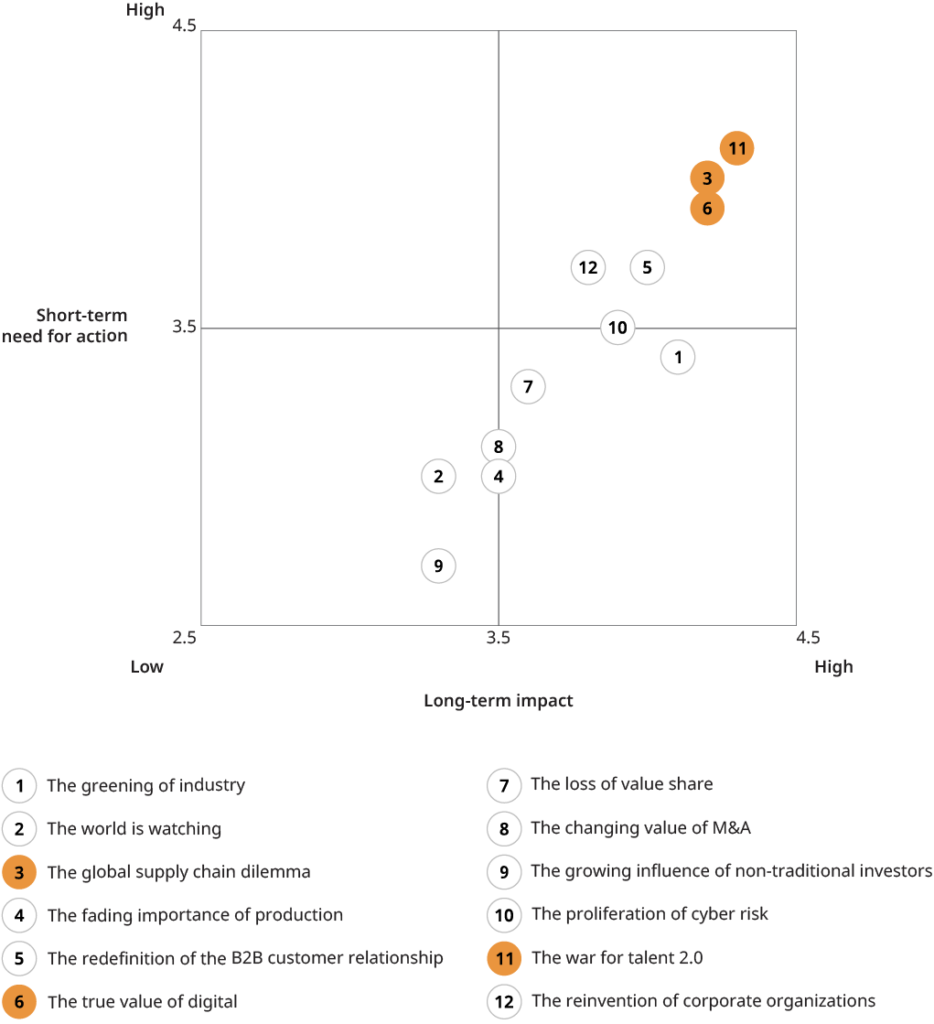

The following three themes have come out as the leading topics in our “impact vs. need for action” ranking. (See Exhibit 2.) We are sharing some of the perspectives that our interview partners shared with us.

Spotlight 1: The war for talent

This theme came out at the top of the ranking. There was wide agreement among the company leaders that the industry faces a substantial shift in skill portfolio and general upskilling ahead. Many traditional skills will become redundant, but company leaders were confident that the shift will happen gradually and be managed organically, without having to resort of greater restructuring efforts. The most commonly raised theme was insufficient access to certain skills, especially but not only those related to digital (for example, data scientists, AI, or cybersecurity experts). Unattractive company locations and the image of “old economy” were quoted as reasons. Another observation that was shared widely was the reluctance of upcoming junior management talent to take on expat positions abroad, as was previously the norm, leading to a lack of international experience. This phenomenon was typically associated with the broader theme of changing attitudes toward work vs. life. On the positive side, company leaders felt they have powerful weapons in the war for talent, such as solidity and value orientation (points that came up repeatedly in interviews with family-owned firms), investment in people and the willingness to leverage new work models, and setting up shop in trendier locations to accommodate new workforce requirements. Some specifically see it as an opportunity to leverage the more down-to-earth attitudes of family businesses to attract top-notch talent (as a counterweight to the large corporations in major urban areas).

Exhibit 3: Hypotheses 2030 ranked by impact and need for action for the manufacturing industry

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

Spotlight 2: The global supply chain dilemma

The recent COVID-19-related supply chain disruptions certainly played a role in bringing this topic so far up in our ranking. Our Manufacturing Industry Strategy Club Pulse Survey, for instance, showed that supply-chain disruptions in more than 50 percent of the responding firms were a key driver for revenue losses, especially at the beginning of the crisis. And this despite the fact that the supply chains of B2B manufacturing fir ms are typically less global and less complex than those of automotive OEMs for e xample. Consequently, few of the companies we interviewed had severe breaks in the supply chain that would have halted production completely. “The frequently denounced shopping around the church spire has its advantages,” one managing director of a leading machinery player cheered. While no disruptive shifts in supply chain strategies were anticipated, it was clear that companies will rate security of supply — and more flexibility as a means to this end — higher going forward (see our article “Making Supply Chains More Resilient”). Depending on the business model, that can mean either more “local-for-local” (for instance in the case of component manufacturers) or more “centralization,” including near-shoring of low-cost sourcing from Asia to Eastern Europe (in the case of complex machine OEMs). And it will lead, wher ever economically feasible, to a move from single to at a minimum dual souring strategies. But there was broad consensus that the new focus on resilience must not come at any cost, as “customers will likely not be willing to pay more.”

One aspect that came up loud and clear in our discussions was the issue of rising political tensions and trade conflicts, with their implications not only on supply chains but on the very business model of many manufacturing firms that are highly dependent on exporting globally. While not the focus of this round of discussions we are planning to make this a topic for future industry dialogue.

Spotlight 3: The true value of digital

There was broad agreement regarding the continued high potential of “digital” for manufacturing companies and around the fact that only a fraction of this potential has been realized thus far. The two elements of our hypothesis (the huge unexploited potential for internal efficiency gains and the limited external revenue potential) can best be illustrated by two supporting quotes. The CEO of a leading provider of intralogistics systems who currently invests heavily in digitally enabled end-to-end processes stated: “We still see 20 percent to 30 percent internal efficiency gains through digital. It takes some time to get there, but I am sure whoever does not invest in this now will be dead in 2030.” On digital business models, the chief technology officer (CTO) of a large manufacturer of mechanical components said, “We are not and we won’t be making much money by selling digital products like software or apps. But digital will allow us to make money with our traditional products in a new way.” However, the digital trend is clearly hampered by “The Proliferation of Cyber Risks” (hypothesis 10) which also has been rated very high, and one CEO noted that the adoption of digital/Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) offerings has slowed due to customer concerns on system attacks or data theft.

Despite the unanimous view that digital continues to be a top topic, our concrete hypothesis was one of the more hotly contested ones. (See Exhibit 3.) But that contentiousness may have been driven by objections against our somewhat brusque denouncement of “data-driven business models.”

Onwards and Upwards

COVID-19 is a reality, and recovery of the economy to precrisis levels will take a few years, as we saw in previous recessions. But long-term growth projections remain intact. The decade will bring old and new challenges for manufacturing firms — and new opportunities, as our 12 themes illustrate. As always, the future will belong to the visionaries, to the adaptive, and to the prepared. Now is a good time for company leaders to take stock, to set the strategic direction, and to prepare for the 2020s. While the future of the industry may be uncertain, there is one thing that is certain: It won’t be boring.

Manufacturing Industries 2030 – Beyond COVID-19 (Download the full report here)

Manufacturing Industries 2030 – Beyond COVID-19 (Chinese) (Download the full report here)

Source from Oliver Wyman

Disclaimer: The information set forth above is provided by Oliver Wyman independently of Chovm.com. Chovm.com makes no representation and warranties as to the quality and reliability of the seller and products.

বাংলা

বাংলা Nederlands

Nederlands English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch हिन्दी

हिन्दी Bahasa Indonesia

Bahasa Indonesia Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 한국어

한국어 Bahasa Melayu

Bahasa Melayu മലയാളം

മലയാളം پښتو

پښتو فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Русский

Русский Español

Español Kiswahili

Kiswahili ไทย

ไทย Türkçe

Türkçe اردو

اردو Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt isiXhosa

isiXhosa Zulu

Zulu